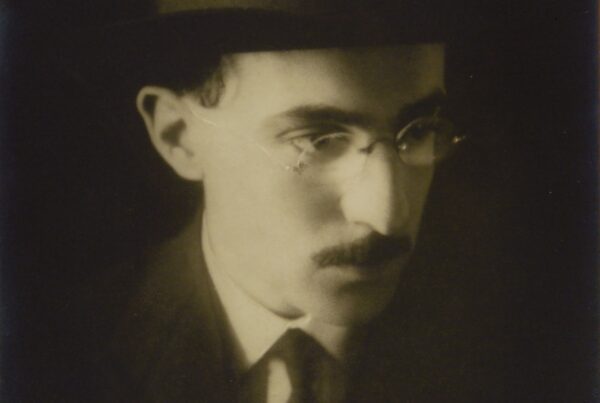

I met him some years ago in his house in the South of England. He was a kind man. He gave me all the instructions I needed to arrive there from Victoria Station, London. After lunch at his house, while waiting for the train, we talked about Graham Greene, his colleague at Section V of MI6. He died on February 27, 2007, aged 96. He worked under “Kim” Philby’s supervision.

I met him some years ago in his house in the South of England. He was a kind man. He gave me all the instructions I needed to arrive there from Victoria Station, London. After lunch at his house, while waiting for the train, we talked about Graham Greene, his colleague at Section V of MI6. He died on February 27, 2007, aged 96. He worked under “Kim” Philby’s supervision.

I quote his obituary from The Times, March 26, 2007: «Linguist, teacher and translator who served with distinction as an intelligence officer during the war and afterwards [January 30, 1911 – February 27, 2007] Charles de Salis’s introduction to the world of intelligence was characteristically opaque. One afternoon in the autumn of 1941, after a cursory interview and medical examination at 54 Broadway, he was told: “You must take the Yoicks bus at 6 o’clock”.

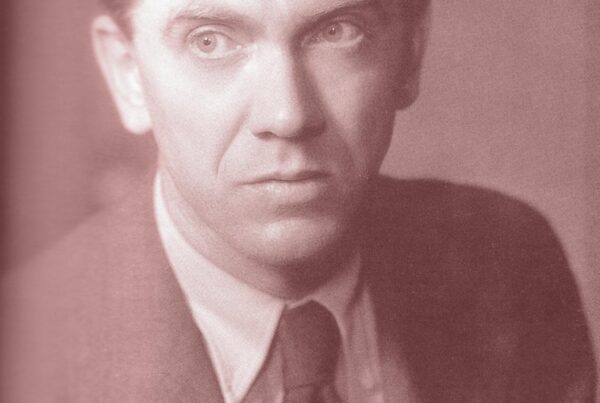

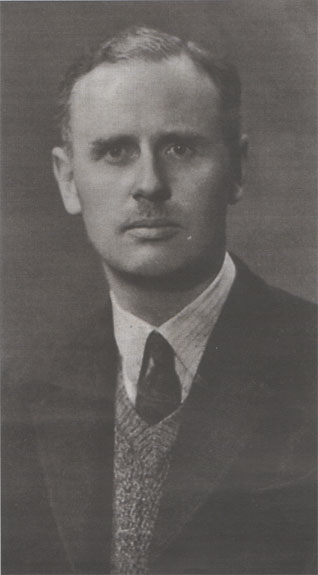

Yoicks turned out to be a suburban villa in St Albans, used as a hostel by secretaries working for the intelligence services. The next day he went to Glenalmond, a larger house the other side of the town, where he met two men who had earlier interviewed him at the War Office. One of them was Kim Philby. De Salis’s task, under Philby’s supervision, was to assemble a detailed account of Axis intelligence activities in Portugal, which were considerable. In this he was aided by agents on the ground, by intercepts of German signal traffic from Bletchley Park, and by the novelist Graham Greene, his immediate understudy. So effective was this combination that by April 1943 SIS was able to compile a comprehensive list of German agents and their controllers, which was handed to the Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar.

By then Salazar realised he had backed the wrong horse and was looking for ways of distancing himself from the Axis powers. The Germans were expelled and their Portuguese agents arrested. Years later, de Salis saw a version of this list, from Portuguese archives, with detailed annotations in Salazar’s hand.

But for the war, Charles de Salis would never have become an intelligence officer. Brought up in Maidstone, Kent, and educated at Maidstone Grammar School, he had gone up to University College, Oxford, in 1929 to read modern languages – French and Spanish – with the aim of becoming a teacher. There, one of his tutors was the eccentric “Colonel” George Kolkhorst, who wore a sugar cube round his neck “to sweeten conversation”. Kolkhorst did de Salis a backhanded favour, awarding him a scholarship for a year at Madrid University, a beneficence only slightly marred by its manner of delivery. “I offered it to Hilton,” the colonel said, “but the silly fool turned it down.”

In Madrid de Salis mixed with some remarkable people, including the poet Federico GarcÍa Lorca, and cemented his love of Spain and Spanish literature. It was his knowledge of Spanish that attracted the attention of the War Office in 1941 when he was an officer in the Intelligence Corps.

At Glenalmond he enjoyed Philby’s company. While the enemy was Germany, Philby’s secret life as a Soviet agent caused no special difficulties. In August 1943 de Salis was posted to Lisbon, under cover as a passport officer. Among others serving there was “Klop” Ustinov, father of Peter, who proved adept at “turning” German agents.

One of SIS’s double agents in Lisbon was Otto John, head of Lufthansa. He came under suspicion from the Gestapo for involvement in the July plot against Hitler and was about to be arrested when de Salis and a colleague managed to hide him and smuggle him away to Gibraltar. John later became head of the West German security service but in 1954 defected (or was kidnapped, as he claimed) to the East – and then defected back again.

Less successful was de Salis’s attempt to save Johnny Jebson, an officer of the Abwehr who worked for SIS as a double agent and was “run” by de Salis. When the Nazi security services, the SD, took over the Abwehr, suspicion fell on Jebson. Decrypts from Bletchley Park revealed he was about to be kidnapped.

De Salis should have been informed at once of the great risk his agent ran, but such was the sensitivity of Bletchley material that the telegram sent to de Salis was deliberately gnomic. “Tell Artist (Jebson’s pseudonym) to be careful,” it said.

De Salis passed on the message. “Am I not always careful?” retorted Jebson. He was later kidnapped, returned to Germany and liquidated. De Salis never forgave the officer who drafted the telegram.

When de Salis was posted back to London in November 1944, the target had changed. Soviet communism and the KGB had taken over from the German intelligence services. Now Philby’s double life began in earnest.

One incident seemed to de Salis to be significant but only in retrospect. A telegram from Cairo indicated a would-be defector from the Soviet Embassy there. Prompt action was needed, but Philby, uncharacteristically, did nothing for 24 hours. Then a second telegram arrived: the man had been put on a plane back to Moscow. A valuable defector, at a time when they were almost unknown, was lost.

De Salis was subsequently posted to Paris, where he gathered material on the French Communist Party, to Copenhagen, and finally, in 1960, to Rio de Janeiro. He took early retirement from the service in 1966 to pursue his love of teaching languages for ten years at Ashford Grammar School.

He lived in Appledore, Kent, and later in Rye, to all outward appearance a donnish former diplomat. He was a modest aesthete, an amusing raconteur and mimic, a generous host to his many friends, in step and loved by all generations.

Asked once by an Abstract artist what he thought of his work, he deftly avoided comment by saying he was “a child of the Enlightenment”.

He wrote poetry and translated works of the Spanish, French and Portuguese writers he most admired. As recently as 2005, when de Salis was 94, a judge in The Times Stephen Spender Prize for poetry translation commended his translation of The Song of Roland.

De Salis married in 1946 Katherine Gange, who had been Philby’s secretary, but she died just six months later as a result of an operation. In 1948 he married Mary Young, who died in 2001.

Charles de Salis, intelligence officer, linguist and schoolmaster, was born on January 30, 1911. He died on February 27, 2007, aged 96»